Snake JARs, Part I: Hidden log4j Dependencies in Python Packages

One of the great things about open source is that we can all stand on each others’ shoulders. So many individuals and organizations build useful things — both open and closed source — that incorporate or vendor other useful things that individuals or organizations have built and open-sourced.

The problem, of course, is that the resulting dependency network is huge. It’s decentralized. And for many organizations and software supply chain vendors, it’s practically impossible to track the right way.

For practical purposes, most companies and information security vendors rely on self-reported metadata. The idea is to use the information provided by developers when they publish the package on something like PyPI or NPM, because they know best, right? Or, more honestly, the alternative is complex and costly…

We’ve spent more than three years now trying to address this issue, in particular, in the Python, R, and NPM ecosystems. For example, for Python, we do much more than just parse requirements.txt files and calculate file hashes. We store the results from static analysis and QA tools and analyze ASTs — yes, even for older versions of Python that are no longer supported by pyqa tooling. And we don’t just look at Python files in Python packages…

What does this mean? Well, let’s talk log4j and Python.

PyPI packages can distribute anything. There are JARs, DLLs, SOs, and executables of every variety. It’s fairly terrifying if you put your risk and infosec hat on.

But PyPI metadata only supports describing Python dependencies, so even when a package author is acting in good faith, how would they let you know that they’re vendoring another package? They don’t mean to omit the log4j dependency, but there’s just nowhere for them to put it given PyPI’s metadata standards.

If you’re using a “normal” tool to analyze security vulnerabilities or generate a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM), it’s probably reading the requirements.txt file or similar metadata from pyproject.toml, Pipfile, or setup.py. But that won’t solve the problem if you’re looking to identify something like a JAR.

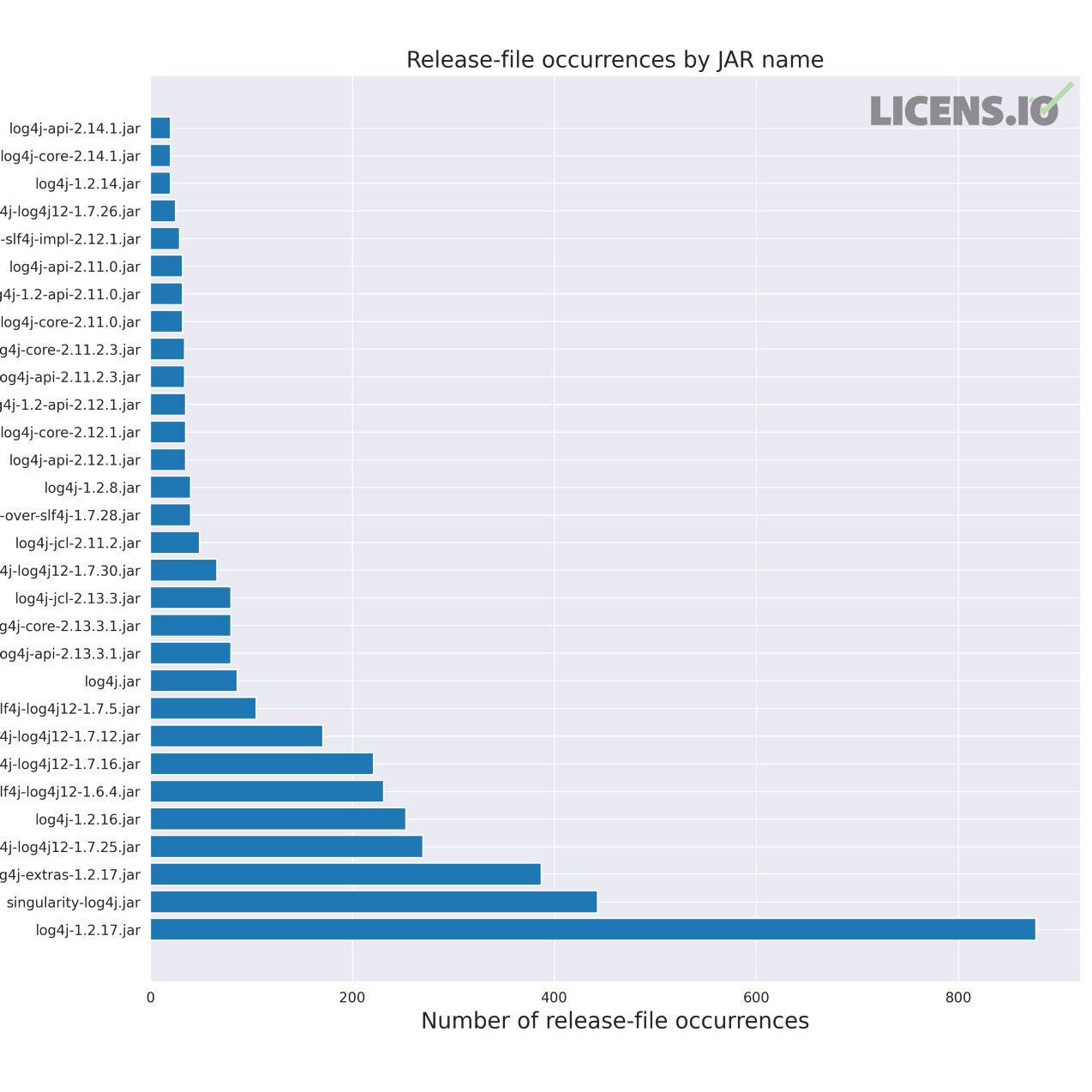

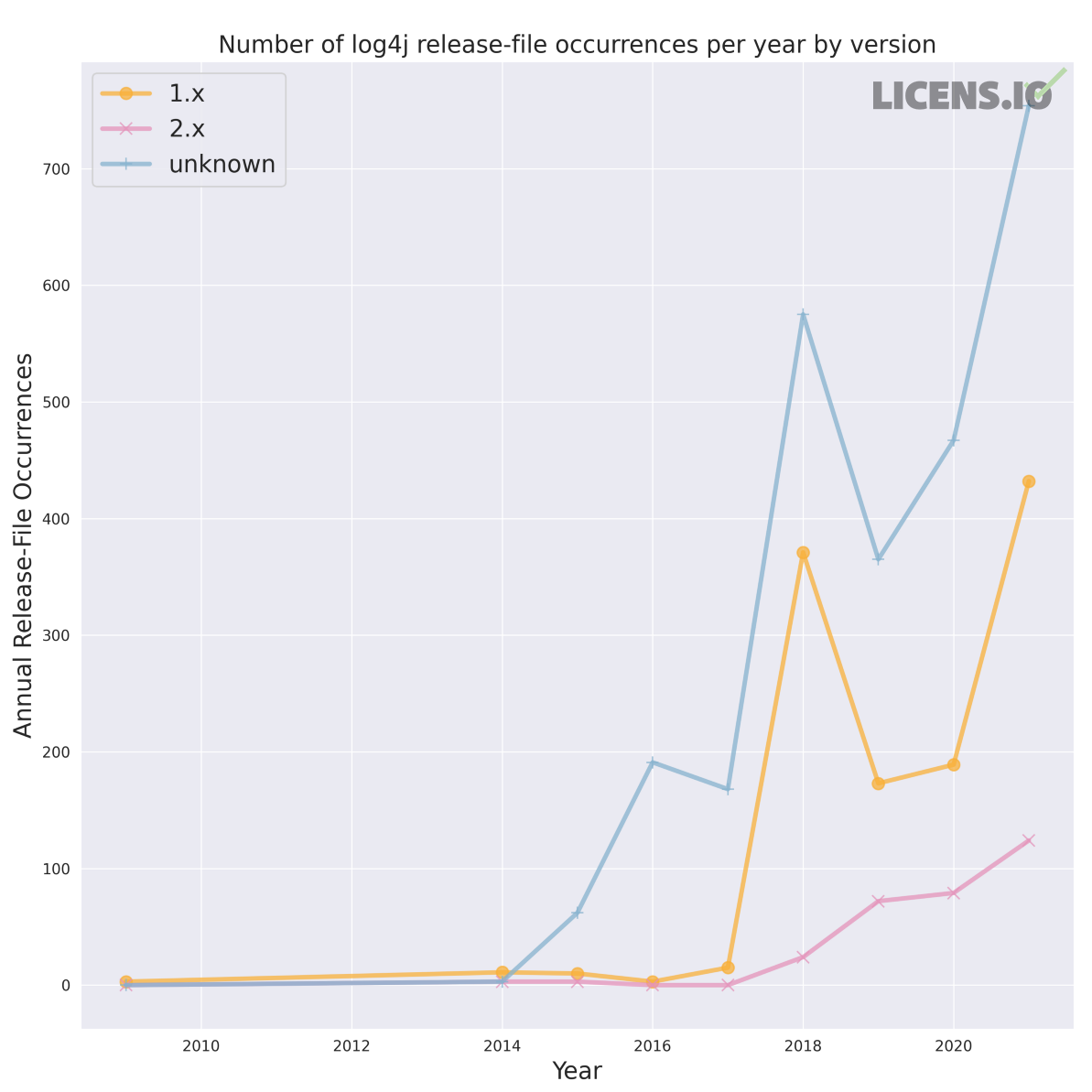

See, for example, the figures below. There are over 60 active PyPI projects that vendor log4j JARs. Across these 60 projects, there are nearly 4,100 log4j-related JARs that need to be identified and possibly updated. Some of these projects are almost certainly not vulnerable based on their configuration or usage, but some probably are…

Log4j is obviously just the package on the tip of your tongue after the last 60 days. If we step back, what does the scale of the Java vendoring issue really look like? And past Java, what other languages or dependencies are vendored in PyPI and Conda packages?

We’ll share more in our next post, as well as how we’re helping address these issues with customers and open source projects in the community.